Dear EarthTalk: What ever became of the Biosphere 2 project in Arizona and what did we learn from it? ~ B.C., Tampa, FL

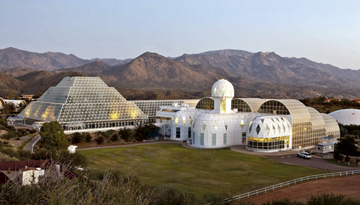

Biosphere 2 project began in 1984, led by John Allen who called it “The Human Experiment.” The project sent eight explorers, or “biospherians,” to live in a sealed ecosystem for two years. The facility they would be living in came complete with an intensive agriculture unit and five separate biomes including a tropical rainforest and a savanna grassland. Early on, Biosphere 2 was the world’s first mini biosphere and became a landmark in the fields of biospherics and closed ecological systems. Many wondered why was it called Biosphere 2 if it was a first. That’s because Biosphere 1 is planet Earth.

The Biosphere 2 experiment was meant to explore the possibility of using closed ecological systems to support and maintain human life in outer space as an alternative to Earth’s biosphere. The three main goals of the experiment were education, eco-technology development, and to learn how well their eco-laboratory worked. The project also hoped to help NASA and other space agencies learn more about life-support systems for long-term space missions.

In 1991, the eight biospherians began what would be their two-year stay in Biosphere 2. The group consisted of four men and four women—five Americans, two Britons and one Belgian. Their plan would be to spend two years studying how a mini-biosphere would work with as few outside inputs as possible. As a fairly new concept, there were many challenges that came with living in an enclosed biome. The facility had to replicate many of Earth’s innate services, such as ocean waves. Each biome had to have the correct temperature and rainfall amounts. The biospherians also had to grow their own food and slaughter their own livestock. Growing their own food was such an endeavor that it required each crew member to work on farming three to four hours a day, five days a week.

Biosphere 2 dramatically expanded scientists’ visualization of what living off-planet would entail. It revolutionized the field of experimental ecology and proved that a sealed ecosystem could work for years, a lesson that the Mars colony planners can build off of. The experiment also provided lessons on how to maintain nature in the grasps of global warming. The biospherians learned how to keep stressed reefs alive, how to protect rainforests, and how to work with plants to keep carbon dioxide levels down.

Since 2006, the Biosphere 2 facilities have been owned and managed by the University of Arizona. It is no longer a closed ecological system, but a facility where ecological systems similar to Earth’s biomes are experimentally researched. These experiments allow scientists to learn more about the effects of global warming out in the real world. In 2023 the University of Arizona launched SAM, a Space Analog for the Moon and Mars. Built around the original Biosphere 2 facility, SAM serves as a controlled environment or greenhouse for visiting research teams to live while conducting individual research projects.

CONTACTS: Biosphere 2’s Lessons about Living on Earth and in Space, https://spj.science.org/doi/10.34133/2021/8067539; SAM Mars Analog, https://biosphere2.org/research/research-initiatives/sam-mars-analog; Biosphere 2: The Once Infamous Live-In Terrarium Is Transforming Climate Research, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/biosphere-2-the-once-infamous-live-in-terrarium-is-transforming-climate-research/.

_______________________________________________

Dear EarthTalk: Is compostable plastic too good to be true? ~ Peter C., Pittsburgh, PA

In recent years there has been a global movement to pressure corporations into becoming more eco-friendly. One of the most frequent measures taken by these companies is limiting the use of single-use plastics and replacing them with so-called compostable plastics. Compostable plastics are frequently confused with biodegradable plastics. Biodegradable plastics are defined by their ability to degrade completely into biomass within a given time frame; compostable plastics are designed to be processed in industrial composting facilities. Many of the alleged “100% compostable,” plastic-like materials are made from polylactic acid (PLA), a polymer derived from the fermentation of various types of starch.

Of the 6.3 billion tons of plastic that have been discarded since the wonder material started being mass-produced in the 1950s, only around 600 million tons has been recycled. Almost five billion tons have been either sent to landfills or left in the natural environment. Plastic production also contributes immensely to greenhouse gas emissions. Aside from the disastrous effects plastic has on the environment, it can also be extremely dangerous to human health. Microplastics from air or water can cause significant damage to cells in the body, causing cancers, lung disease and birth defects. Residents of “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana face the highest rates of cancer in the U.S., largely as a result of the plastic production plants along the lower Mississippi River.

Compostable plastic—which would theoretically leave no trace on the environment—sounds like a great solution. However, it isn’t as simple as it sounds. While plastic-like materials like PLA will decompose in the right conditions, it’s rare that PLA is disposed of correctly. Putting a cup made of PLA in your home compost won’t break it down as it requires a specific set of microorganisms used in industrial composting that need temperatures well above what most home composts can reach. A UK-based science experiment from 2022, “The Big Compost Experiment,” had citizens carry out home compost experiments to test the performance of compostable plastics. The public was generally very confused about what was compostable and what wasn’t, and many of the objects labeled as “home compostable” did not fully disintegrate into their compost bins.

What needs to change to make compostable plastics a more viable option for the future? First off, there are very few facilities in the U.S. that are set up to handle the disposal of PLA products. Research by BioCycle magazine found that only 49 out of 4,700 composters nationwide accepted compostable plastic products. The good intentions of using compostable plastic don’t make a difference if the waste system isn’t set up to process it. Because so few facilities accept PLA, much of it ends up in landfills. It is also difficult to distinguish between regular and compostable plastic. When regular plastic gets into composts it can cause soil and waterway pollution. So, yes—compostable plastic is too good to be true. However, improvements in waste system infrastructure could enable them to play a more effective role in the future.

CONTACTS: Home Compostable Plastics Are Too Good to Be True, www.treehugger.com/home-compostable-plastics-too-good-true-7096891; Your compostable cups and containers aren’t reversing the plastic problem, www.popsci.com/environment/truth-about-compostable-cups/; Why biodegradables won’t solve the plastic crisis, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191030-why-biodegradables-wont-solve-the-plastic-crisis.

_______________________________________________

EarthTalk® is produced by Roddy Scheer & Doug Moss for the 501(c)3 nonprofit EarthTalk. See more at https://emagazine.com. To donate, visit https://earthtalk.org. Send questions to: question@earthtalk.org.